How a Grinnell student captured Olympic glory in Paris 100 years ago

Frederick Morgan Taylor 1926

Frederick Morgan Taylor 1926

July 31, 2024 — During his time as a Grinnell College student, Frederick Morgan Taylor 1926 sang first tenor with the Glee Club, starred in a play called The Goal, studied English and business administration, and was known for dancing the best Charleston on campus.

He also was the fastest hurdler in the world.

100 years ago this month, Taylor became the first American to win a gold medal at the 1924 Olympics, running the 400-meter hurdles in record time. Those games were in Paris just like the 2024 Olympics Grinnellians are watching a century later.

“That makes it the perfect time to shine a spotlight on F. Morgan Taylor’s tremendous accomplishments,” says Evelyn Freeman, former Grinnell College women’s cross country and track and field coach. “With the Olympics back in Paris it’s a full circle moment, and a chance to celebrate and bring attention to the most decorated Olympian in the history of the College for new generations of Grinnellians.”

Taylor was chosen as the U.S.

Taylor was chosen as the U.S.

flag bearer for the 1932

Olympics in Los Angeles.

Taylor’s hurdling heroics didn’t end in Paris. After graduating from Grinnell, he went on to add bronze medals at the 1928 and 1932 Olympics, becoming the first U.S. track athlete to win medals in three Olympics. No one else matched that accomplishment until Edwin Moses in 1988.

Well known nationally in the 1920s and 1930s, Taylor was chosen to be the U.S. flag bearer at the 1932 Olympics in Los Angeles. He had a Hollywood lunch with Gary Cooper 1926, played a round of golf with Arnold Palmer, was referenced in the movie Chariots of Fire, can be found in several halls of fame, and is the namesake of a major award given to Pioneer student-athletes annually.

His athletic feats have stood the test of time. He is still the College’s record holder in the long jump (25-2 in 1925) and is fourth in Grinnell’s track record book in the 400-meter hurdles (53.89 in 1924).

In a 1984 article in The Iowan, Ray Obermiller, Grinnell’s cross country and swimming coach at the time offered this assessment of the Olympic champion. “Taylor’s records were not only great in the 1920s they would be very competitive today. And this is all the more extraordinary when we remember Taylor didn’t have the vastly improved runways, pits, starting blocks, track surfaces, and training methods we have now. The man was just an amazing athlete.”

But we’re racing ahead. Let’s first go back to the starting blocks and get to know Taylor and what it was like to win a gold medal 100 years ago.

The road to the Olympics goes through Iowa

Taylor was born and raised in Sioux City, Iowa, where his dad operated a cleaning business. Coached in high school by Grinnell alumnus Chuck Hoyt 1918, Taylor already excelled in track.

He first attended Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. It wasn’t to his liking, so Hoyt urged Taylor to enroll at Grinnell, which he did in spring 1922. In addition to track, Taylor played football for the Pioneers and was regarded an ace pass catcher. In 1925, he grabbed a 40-yard throw that helped the Pioneers defeat Iowa State, 14-13.

Taylor was coached by H.J. “Doc” Huff 1909 who became Grinnell’s track coach in 1912 and served as athletic director from 1914-1926. Les Duke 1925 was Taylor’s teammate and became track coach in 1926. The trio are all in the Grinnell College Athletics Hall of Fame.

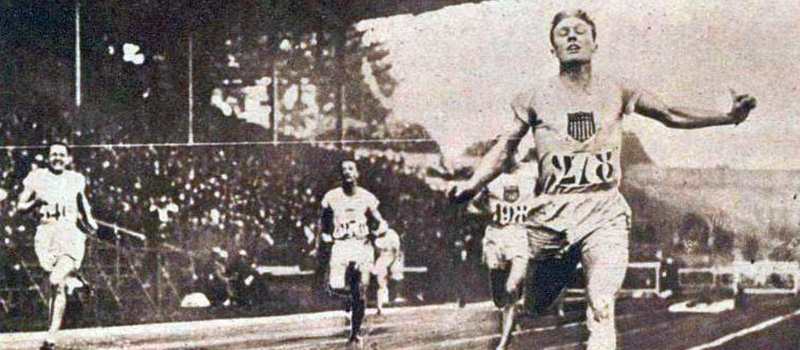

Taylor, left, sprints to the finish line at the 1924 U.S. Olympic Trials in Boston.

Taylor, left, sprints to the finish line at the 1924 U.S. Olympic Trials in Boston.

Taylor’s quest for the Olympics began with a sectional tryout in Iowa City on May 30-31, 1924. Three Grinnellians competed and advanced: Taylor in the 400-meter hurdles, Foster Rinefort 1927 in the discus, and Leonard Paulu 1922 in the 100-meter dash.

Next it was on to Boston for the final Olympic tryouts. Listed in the program for fans that day was a misprinted G. Taylor instead of the F. Taylor he normally went by. Nonetheless, Taylor qualified for the Olympics while Rinefort barely missed out qualifying. Paulu missed the finals because of a personal matter.

Taylor was one of 107 U.S. track athletes that sailed across the Atlantic Ocean aboard the S.S. America in June 1924. The voyage took nine days. After arriving in France, the U.S. team traveled by train to Paris and stayed at the Chateau de Rocquencourt, once home to one of Napolean’s generals.

The race and the *world record

At 2:45 p.m. Paris time (7:45 a.m. in Iowa) on Aug. 9, 2024, athletes from several countries will take their place at the start of the 400-meter hurdles final. It will be televised around the globe, and the results will be shared on social media quicker than the time elapsed in the race itself.

Things were quite different a century ago. In 1924, 44 nations sent athletes to compete in 126 events across 17 Olympic sports. More than 3,000 athletes competed. (For comparison, in 2024, 206 nations sent athletes to compete in 329 events across 32 sports. More than 10,500 athletes are competing.)

F. Morgan Taylor 1926 crosses the finish line to win the gold medal in the 400-meter hurdles at the 1924 Olympic Games held at Stade Olympique Yves-du-Manoir in Paris.

F. Morgan Taylor 1926 crosses the finish line to win the gold medal in the 400-meter hurdles at the 1924 Olympic Games held at Stade Olympique Yves-du-Manoir in Paris.

American sporting dominance was on full display in 1924. The U.S. had the most medals (99) followed by France (38) and Finland (37). The U.S. also won the gold medal race with 45. No other country had more than 14.

Taylor and his competitors didn’t have to wait long to compete. The opening ceremonies were July 5, and one day later 23 hurdlers from 13 nations began competed at the Stade Olympique Yves-du-Manoir. The competition featured the three-round format: quarterfinals, semifinals, and a final. Ten sets of hurdles were set on the course. The hurdles were 3 feet tall and were placed 35 meters apart beginning 45 meters from the starting line, resulting in a 40 meters home stretch after the last hurdle.

Taylor ran a 55.8 in the quarterfinals and a 54.9 in the semifinals to advance. The world record at the time was 54 seconds flat. The six competitors in the finals were Taylor, two University of Iowa hurdlers, Charles Brookins, C.F. Coulter; Ivan Riley (also American); Erik Wilén of Finland; and Charles Blackett of Great Britian though Blackett was disqualified for two false starts.

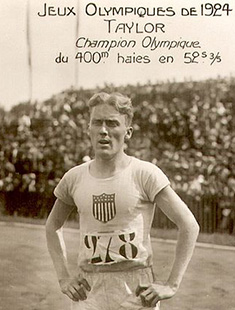

Taylor’s victory and time is

Taylor’s victory and time is

commemorated in a French

publication.

With a clean start, Taylor broke the tape 52.6 seconds later, with his arms outflung and his head thrown back. But he had overturned the next-to-last hurdle. That wasn’t a big deal in terms of the race result; the gold medal was his. But the rule of every hurdle must remain standing prevented him from having the world record. That rule was eliminated in later years.

Brookins and Wilén also broke the world record time, but Brookins, who had crossed the finish line in second, was disqualified for running out of his lane. So Wilén, who finished the race third initially, claimed the record (53.8).

(Taylor would win the world record eventually though by running the 400 meters intermediate hurdle race in 52 seconds flat at the 1928 Olympic trials in Philadelphia. The current world record is held by Karsten Warholm from Norway, with a time of 45.94 seconds in 2021.)

With his race over two days after the Olympics began, Taylor had some time on his hands before sailing back to the U.S., so he went to England for two purposes. One was to visit the home of his forebearers. Taylor’s father had emigrated from England. The second was to compete (and win) in the steeplechase race at Stamford Bridge. Taylor then returned to Paris for the presentation of the gold medal before going to Ireland where he competed in 10 races over two days. He won all 10.

A hero’s welcome

After sailing back to the U.S. aboard the S.S. Aquitania, Taylor snuck in one more track meet in New Jersey. Then on Sept. 8, he returned to Sioux City where he was met by his parents, a band, city council members, chamber of commerce representatives, the police chief, and a large crowd of friends.

“I can run, but I can’t make a speech,” declared Taylor, when insistent cries of “Speech!” “Speech!” compelled him to say something to the crowd, according to the next day’s Sioux City Journal. Following a reception at the station, a parade led by motorcycle policemen escorted the champion hurdler to city hall.

Upon his return to campus that month, Taylor told the Scarlet & Black what he learned about French fashion, and talked about his various experiences like riding horseback on the Boise de Boulogne and attending a tea dance at Savoy in London. Athletically, he picked up where he left off winning the 220-meter hurdles at the 1925 NCAA Championships.

After graduating in 1926, Taylor began his career selling ads for the Chicago Tribune. In 1929, he took a job as an English teacher and track coach in Quincy, Illinois. He taught until 1939 when he took a position with Marshall Field & Company in Chicago. He started by filling orders and wrapping packages before working his way into management.

Taylor’s actual Olympic uniform – sweater, shorts, and shoes – are displayed in the Grinnell College athletics office. Plans are underway to move the display into a public area in the Bear Recreation and Athletic Center.

Taylor’s actual Olympic uniform – sweater, shorts, and shoes – are displayed in the Grinnell College athletics office. Plans are underway to move the display into a public area in the Bear Recreation and Athletic Center.

After 16 years at Marshall Fields, Taylor moved to Rochester, New York, to work for Sibley, Lindsay & Carr, a large department store. He moved up the ranks to become assistant to the president and later manager of Sibley’s Irondequoit branch store. Officially retired in 1972, he still worked part time at G.A. Kayser & Sons until his passing in 1975.

Taylor had three sons and a daughter. The eldest, Frederick Morgan “Buzz” Taylor Jr. nearly was an Olympian himself, ranking fourth in the world in long jump in 1952 and 1953 while a student at Princeton.

A Rochester newspaper interviewed Taylor Sr. in 1958 and 1960 when his son, Arch, played high school football and track. There are a lot of reasons for advancement in the track world, Taylor said at the time.

“It’s the coaching, the specializing in events, and the desire to excel, which youngsters have come up with in the last decade,” he said. “Athletics like business needs discipline, you keep pushing, you keep on trying.”

At the invitation of Les Duke, Taylor returned to Grinnell many years after graduation to spur more participation in Pioneer sports. He talked more about the future of sports than his own accomplishments.

But Taylor’s accomplishments still are resonating. In 2021, he was named to the Missouri Valley Conference (MVC) Hall of Fame. He’s also been inducted to the Helms Foundation National Hall of Fame, the National Track Hall of Fame, and the Sioux City Relays Hall of Fame.

“He had a lot of heart, a lot of determination,” recalled his brother Warner Taylor in a 1989 Sioux City Journal article. “I think his talent came from our mother. We used to run away from her all the time.”

— by Jeremy Shapiro

For your information

Newsreel footage of the 1924 400-meter hurdles race Taylor won can be seen on an Olympics website, though a (free) sign-in is required.

The F. Morgan Taylor ’26 Award is presented each year to Grinnell College student-athletes for outstanding athlete in a single sport. Runner Brian Goodell ’24 and swimmer Ethan Yuen ’24 were the 2024 recipients.

To read more alumni news, check out our news archive and like the Alumni & Friends Facebook and the Alumni & Friends Instagram accounts.