Oldest living woman Marine is a 1941 Grinnell College graduate

Editor’s note: Betty Printz Sims ’41 passed away on Dec. 4 at the age of 104. “My mom loved Grinnell,” says Bekki Sims. “To have a story written about her by a Grinnell alum for Grinnell at the end of her life surprised her and made her so very happy. It seemed sort of full circle.”

October 30, 2023 — In December of 1941, Betty Printz Sims ’41 was a recent Grinnell College graduate teaching in Tripoli, Iowa. She remembers lying in bed while listening to the radio.

Betty Printz Sims ’41

Betty Printz Sims ’41

“I was trying to keep warm because the landlady wouldn’t turn up the heat,” she describes in a 2007 Veterans History Project interview. The radio show was suddenly interrupted with news of the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

“Her first thought was, ‘Where the heck is Pearl Harbor?’” says Betty Printz’s daughter, Rebekah “Bekki” Sims, who has heard this story recounted dozens of times. The next day, Betty Printz sat with the school children listening to President Franklin D. Roosevelt give the “Day of Infamy” speech, which led to Congress declaring war against Japan and entering World War II.

“I decided I didn’t want to continue teaching music in a little town in Iowa,” Betty Printz explains. “I wanted to do something constructive for the war effort.”

Born in 1919 in Sac City, Iowa, Betty Printz (then known as Betty Printz Long) attended an all-women’s Christian college in Missouri for two years before studying at Grinnell from 1939-41. The oldest living female Marine, Betty Printz is celebrating her 104th birthday on Oct. 30.

“We are bringing her dinner and ice cream cakes,” Bekki says about today’s birthday plans. “She’s gotten many, many cards especially from other women Marines.”

Printzy in the 1940s

Printzy in the 1940s

In the summer of 1943, upon completing her teaching contract, Betty Printz headed to Des Moines to enlist. She refused the options expected of her, such as the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps headquartered in Des Moines. Her goal was to join the Marines, following the footsteps of an ancestor who had fought in the Revolutionary War. A few weeks later, she was headed to Camp Lejeune for basic training. There she entered the classification of aviation, hoping to become a control tower operator. Instead, she was placed as a fixed gunnery instructor, learning how to operate a synthetic training device.

And this was how “Printzy,” her nickname in the Marines that became her preferred name ever since, got into the rare field of training fighter pilots to learn how to shoot accurately while flying. In the simulation, she would sit in front of them, creating experiences with enemy aircraft on a screen where she would try to throw them off by deflecting their shots. She was stationed at an auxiliary base in Kinston, North Carolina, where seasoned pilots were sent to train with her and other female gunnery instructors.

“They found this insulting,” Printzy explains. “Many of them had come back from the Solomon Islands and Guadalcanal, where they were shooting by the seat of their pants. And then they were sent, number one, for training and, number two, to women to train them.”

As a further affront to these pilots’ egos, Printzy was only a lower-ranked corporal while they were officers. She had been through officers’ training herself, but ultimately was denied that rank. “I was bilged, as they say,” she explains, describing the sabotage in that time that was par for the course for many women trying to move up. This included having ink purposely spilled all over the work she had to turn in the next day, coupled with her being reported for returning one night after curfew. “There were no excuses, so I stayed a corporal,” she says.

Printzy in her World War II

Printzy in her World War II

Marines uniform

Yet Printzy was still able to gain some footholds while on the base. As a gunnery instructor, she had to operate a stick, which was difficult when wearing the mandatory uniform skirt. “We sent a letter to the C.O. to get permission to wear a man’s pair of pants.” The request was granted, but they still had to show that letter at the mess hall to convince the sergeant to allow them in.

“She had a side to her that we called her marine side,” Bekki explains. “She didn’t take any guff or disrespect. I could talk to her about my school peers and their behavior, and she always had a good perspective.” Sims describes her mom as fair and kind but also not allowing much to intimidate her.

After her military service, Printzy moved to New York City and lived in a one-bedroom apartment with six women Marines. “They rented art for the walls and painted the place red and green,” Bekki recalls from her mother’s stories. Printzy took a job at Schirmer’s Music Store after stopping a man standing outside and asking him where she could find the personnel office. That man turned out to be Gus Schirmer himself, who later interrupted the middle of her interview to say she was hired.

Two years later, Printzy met her husband, Ralph Edwin Sims. He was in the Navy, meaning he had a new assignment every three years. They started out in Virginia, where their daughter Sarah was born. Then they moved to Bremerhaven, Germany, where Ralph assisted the Germans in military reconstruction. Bekki was born in Germany, and Printzy started a nursery school while continuing with her music.

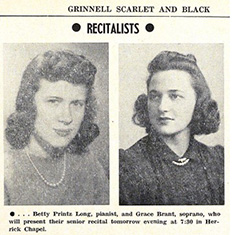

Betty Printz (left) appears in the

Betty Printz (left) appears in the

1941 Scarlet & Black

A music education major at Grinnell, music has remained a constant in Printzy’s life, even while in the Marines, where she organized singing groups to perform in shows, including a trio in which she sang and played piano. “I remember her always playing the piano, but her job was a vocal music teacher in public elementary schools for most of her career,” Bekki recalls.

A 1940 Scarlet & Black article gives notice Betty Printz will be giving a joint recital with Abgail Gilchrest at Herrick Chapel. Betty Printz’s piano performance that day included “Prelude” by Bach; and “Should We Prepare for War” by Liszt. She also played the piano for other students who were giving singing recitals and was part of the Glee Club. Other S&B articles from that time mention Betty Printz was on a social committee for the fall 1940 international relations conference and attended the Flunk Day Pep Meeting in 1941.

As late as 2009, Printzy was still a vocal instructor at a Catholic school, and when she moved into her retirement community, she continued to entertain. “She loved putting on musicals and hosting singalongs into her mid-90s,” Bekki says. “She infused American history into much of what she taught as well as these singalongs. She is a real patriot.”

When her husband died in 1985, Printzy retired from her teaching job at age 66. She embarked upon traveling once or twice a year with two other friends. “They didn’t have a lot of money, so it wasn’t fancy travel,” Bekki explains. “Still, my mother likes to say that she’s ridden an elephant, a camel, and been in a hot air balloon!”

This summer, Printzy was honored in Washington D.C. as the oldest living woman Marine, receiving a certificate that recognizes her as a living legend. She still carries with her that sense of what it means to serve, describing it as a time of “cooperation and unanimity,” even while acknowledging the continued challenges of women Marines, some of whom were there that day to pay their respects.

At an event this summer, Betty Printz Sims ’41 was honored as the oldest living woman Marine. A news station was on hand for the celebration, as were several other women Marines.

At an event this summer, Betty Printz Sims ’41 was honored as the oldest living woman Marine. A news station was on hand for the celebration, as were several other women Marines.

“I recently told her she’s been an amazing mom and grandma,” Bekki says. “I’ve had so many opportunities as an adult to get to know her better and value the stories of her life. It’s a wonderful gift.”

— by Melanie Drake ’92