Hands-on student research helps show viruses can’t survive for long on copper surfaces

It’s midmorning on the last day of April, and Zina Ibrahim ’17, a research fellow in the Food and Drug Administration’s Office of Blood Research and Review, is working from her parents’ home in Atlanta. She’s grateful to be with family during the coronavirus pandemic, and today she’s thrilled for another reason: Ibrahim just found out she’s been accepted to medical school at nearby Emory University.

It’s a career path that started when Ibrahim participated in the Grinnell Science Project (GSP) — a preorientation program for underrepresented science students — and continued when she met Shannon Hinsa, associate professor of biology and a co-director of the GSP that year.

“I fell in love with microbiology through her biology intro class,” explains Ibrahim. “She asked me after one semester if I was interested in being a research assistant in her lab. I worked in her lab for the rest of my time at Grinnell.”

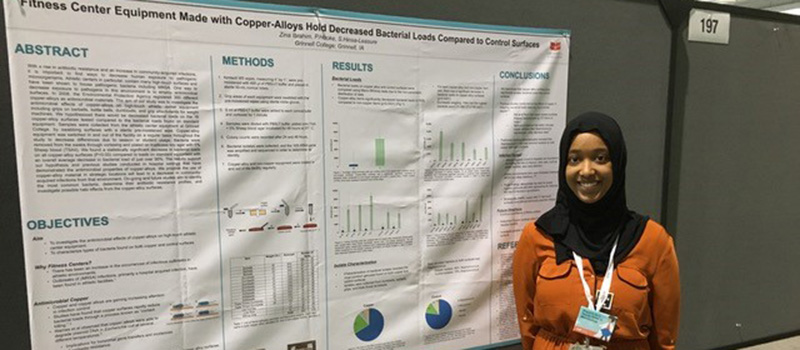

That led to Ibrahim’s partnership with Hinsa on a Mentored Advanced Project (MAP) investigating the ability of copper alloys to reduce the bacterial burden associated with high-touch athletic center equipment. It resulted in a paper co-authored by Hinsa, Ibrahim, Alexandra (Julia) Petrusan ’18, and Patrick Hooke ’15. Ibrahim presented the research findings at the 2016 American Society for Microbiology Microbe Conference in Boston.

Zina Ibrahim ’17 poses with welcome signs to the 2016 American Society for Microbiology Microbe Conference in Boston.

Zina Ibrahim ’17 poses with welcome signs to the 2016 American Society for Microbiology Microbe Conference in Boston.

It’s a topic that’s especially intriguing these days: Studies have shown that a variety of viruses, including coronaviruses, can’t survive long on copper surfaces.

Hinsa, an environmental microbiologist, had studied how bacteria survived in Siberian permafrost, but she wanted students to do hands-on research in local environments — like the College athletic center. For the experiment, copper alloy grips were placed on dumbbells, kettlebells, barbells, and other attachments and compared to equipment with stainless steel grips and weights.

“Hands are sweaty and you’re shedding skin, and it’s hard to clean all those nooks and crannies on the weights and grips,” Hinsa explains about how bacteria accumulates.

For 16 months, Ibrahim, Petrusan and Hooke, who started the project, took swabs of surfaces and brought them back to the lab. “We found that copper alloys reduced bacteria loads by 94% compared to normal surfaces. It was huge,” says Ibrahim. And 99.9% of bacteria are killed within two hours on a copper alloy surface, says Hinsa, who previously ran a similar study with students at Grinnell’s hospital.

Zina Ibrahim ’17 stands with a presentation exploring using copper as an antibacterial surface.

Zina Ibrahim ’17 stands with a presentation exploring using copper as an antibacterial surface.

“These studies are exciting because students get to see an immediate impact of their work at the hospital and the athletic center,” Hinsa says. “Their research helps move the field forward.”

Ibrahim credits Hinsa with shaping her identity as a scientist. “She was really tough sometimes. She told me to do things for myself, so it gave me a sense of figuring things out on my own. That’s really important now at the FDA, because I’m constantly analyzing literature and designing and implementing my own projects. Grinnell is a place where you can really cherish those relationships with faculty and work with them one-on-one.”

“My students become my extended family; and with many, like Zina, I am blessed to have continued that relationship for years after they leave Grinnell,” Hinsa says.

— by Anne Stein ’84